Selective mutism is usually diagnosed in the preschool or lower primary school years. Parents often notice symptoms during this time as children are expected to interact with others.

Signs and symptoms of selective mutism may include:

- Not speaking in at least one social situation where they are expected to speak. This happens even though the child speaks normaly in other settings, like at home.

- Predominantly using non-verbal gestures like nodding, shaking their head and waving to respond

- Not speaking, even in situations where they are being directly assessed

- Having difficulty initiating contact with people and asking questions for themselves

- Avoiding or having difficulty maintaining eye contact

- Often seeming anxious, appearing timid or shy

- Going into 'freeze' mode, becoming motionless and expressionless

If these behaviours last for at least a month, go beyond the first month of school and interfere with schoolwork or social communication, consider having a discussion with a school counsellor before seeking help from a psychologist or psychiatrist for a formal assessment.

There is no single cause for its development; multiple factors may play a role. These include psychological factors, or a shy, or anxious temperament. A family history of selective mutism and social anxiety may also increase the odds.

Environment and family factors can also play a part. For example, the child may have few opportunities to interact socially or face stressful life events that worsen anxiety. For some children, speech and language disorders such as stuttering may contribute to selective mutism.

Contrary to common misconception, the child does not naturally "outgrow" it without support. Selective mutism is not just normal shyness. It is caused by high social anxiety that makes it hard for the child to speak.

When caregivers do not treat selective mutism, children often struggle with communication and social interactions. These skills are important for healthy development as school and social life can be severely impacted. Even simple tasks can be difficult for a child who is unable to speak. For example, asking to go to the toilet can be a challenge. Ordering food in the school canteen and making self-introductions can also be hard.

Over time, anxiety and frustration can grow. This may lead to low self-esteem in the child. They may also become victims of bullying, according to A/Prof Daniel Fung, Senior Consultant at the Department of Developmental Psychiatry.

"Their ingrained, non-speaking habits may also become entrenched over time. Many do not outgrow selective mutism on their own. In fact, the later they receive help, the lower the chances of success," he said.

With the right treatment and support, especially when started early, many children with selective mutism show improvement. According to A/Prof Fung, at least two thirds of children recover from the disorder almost completely with intervention.

"It's almost like learning to ride a bicycle. They make a breakthrough themselves, usually in secondary school, partly with the encouragement of friends who help them come out of their shell," he said.

In older children, teenagers and adults, selective mutism may require more intensive treatment to see improvement.

Treatment for selective mutism usually includes psychological therapy, and in some cases, doctors may also prescribe medication to improve underlying anxiety. The goal is to help the child feel less anxious and pressured when speaking in certain situations.

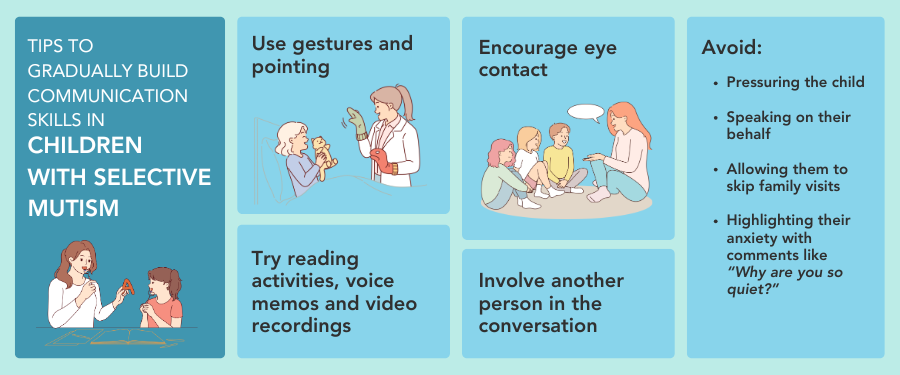

A step-by-step plan helps the child learn to speak normally. Each step builds confidence without adding pressure. For example, the child can start with non-verbal responses like nodding and waving. Then they can move on to mouthing words, whispering, and finally speaking out loud.

Therapy may also gradually include activities that help young children become more comfortable with others hearing their voice. These could involve reading activities, sharing of voice or video recordings of the child.

For older children, cognitive strategies can help. This includes learning to identify anxious or unhelpful thoughts about speaking, and modifying them with more helpful ones. Speech and language therapy may come in handy, if the child also has speech and language difficulties or a communication disorder.

In addition to therapy, support, consistent engagement and motivation from parents and family is key. A/Prof Fung offers some do's and don'ts to build communication skills:

- Start with eye contact: Teach the child to make eye contact with the perosn they want to communicate with.

- Use gestures: For example, simulate eating when hungry or point at something that needs attention.

- Try 'conversational visits': Include another close family member in a conversation the child is already having. This may help the child to gradually feel more comfortable in social settings.

- Celebrate small wins: Remember, each step the child completes is a step forward.

- Don't pressure or bribe the child to speak. This may increase anxiety.

- Don't speak on their behalf nor allow them to skip family visits, as these actions perpetuate the avoidance of the fear of speaking.

- Don't highlight their self-consciousness and anxiety about speaking with comments like, 'Why are you so quiet?'